Not long ago I hiked down a gameland trail into a gorge thick with hemlock and rhododendron to look for a small creek named Devil’s Hole. The name comes from the way the creek emerges through rocks via an underground aquifer and disappears under the earth a few more times throughout its course to join another creek curiously named Paradise.

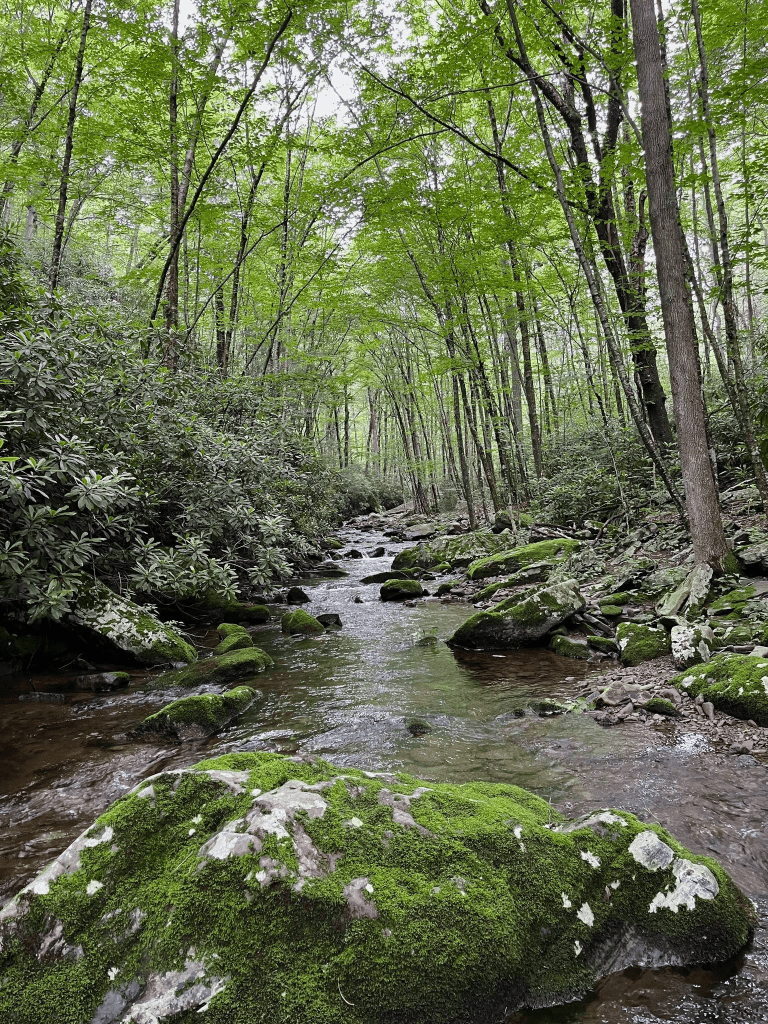

After a good rain, Devil’s Hole is still only 10 feet at its widest. It tumbles over and around boulders of Devonian sandstone left there when the Pocono formation was rearranging itself like a dog getting comfortable on a sofa. The topography creates plunge pools, short shallow runs, cascade falls a few feet high, and cutbanks shadowed by the bent elbows of mountain laurel. It is a remote, mysterious, and beautiful place.

I went there looking for brook trout–small, wild jewels far away from the stocked waters where most anglers go. As a catch-and-release fly fisher who likes to avoid people, this kind of angling is more about the experience than about catching fish. I go to observe the motions –water on stone, current on insect, stillness and rise– form and content defining each other.

Water in motion, like poems, is made of multiple currents, obstacles, fast sections and slower spots. The center channel may be deep or shallow. A gravel bottom holds different insects than a silt bottom. Boulders hide small pockets of stillwater. The steep bank is hard to enter, and then again hard to climb out of. Understanding those variations and learning to use them is what anglers call “reading the water.”

Because I know the region pretty well I already knew what kinds of fish and aquatic insects it would hold for the time of year. That’s the kind of knowledge that comes from having read a library’s worth of rivers.

But, as with a good poem, you can’t know everything ahead of time. At some point you’ve read enough Mary Oliver poems to know what you’re getting into when you enter one, but nothing prepares you for “The face of the moose is as sad / as the face of Jesus.” in her poem Some Questions you Might Ask.

So you read each water anew.

“One question leads to another.” says Oliver. Like a good poem, moving water asks you questions over and over again. What will the current do if I mend my line upstream? Will that boulder hide a trout or a hellbender? Can this log support my weight, or am I going to get wet?

I want poems to prompt questions the way a river or creek does. A stanza break, a caesura–these are moments in motion. Moments when you read the currents around them, observe the words doing things to each other, doing things to you, forcing a response. An enjambment is a bend around a boulder; a stanza break may be the stone you cross to continue on the other side. Form is what gets you there, what shapes your approach to the water.

But as any angler knows, some creeks don’t give up their answers easily, though hopefully their questions invite you back to give it another try. Sometimes you land the fish. Sometimes you don’t. Draft, fail, revise.

I encourage my poetry students to be observers and questioners. Why is this element here? What does it do? How does it affect what comes next? It takes time and practice to understand the machinations of water in motion. It’s the mixture of patience and humility that smooths a rough impatient stone.

Lately, I’ve been moving away from leading workshops with the goal of re-engineering a poem, and more toward learning to read it. And also asking the writer to think about why they wrote it the way they did. As an angler, the better you get at reading rivers, the more you’ll appreciate each new water you step foot in, and the better you’ll be at teasing a fish out of it. As a writer, as you learn how water works, you get better at making it work for you.

That trip down to Devil’s Hole included half a dozen creek crossings. I found bear scat along the bank, a few trout in places I expected them to be, and some where I didn’t. It’s that combination of recognition and surprise that makes a good experience on the water. I lost one fish, probably the biggest one of the day, and the strike still sends jolts into me when I think about it.

And I think about it a lot.

My latest book, Temporary Shelters, is now available at Bookshop and Amazon.