It’s manuscript submission time, which for me, means figuring how much I can afford to spend this year on contest and reading fees. So this seems like a good opportunity to talk about poetry books and money, especially for people new to this game.

Friends and family who aren’t authors, and friends who are authors, but trek in the novel world, act surprised when I joke about how little poets make from their books. There are of course poets who make a decent amount of money on books, but they’re rare. A recent article in The Guardian claimed that poetry sales are booming these days, but booming in comparison to what? It’s a small boom when you compare it to popular novels, celebrity biographies, or the latest political tell-all. And most of the top sellers in poetry are either by dead people (Leonard Cohen, Seamus Heaney, Homer) or Instagram poets, not the typical small-press publishing poet in the US.

I’d guess there are maybe a dozen poets in the US who can live off their poetry book sales, maybe 11 now that we lost Mary Oliver. There are maybe 50 more who make a decent amount of money traveling around doing readings at universities (the only places that pay poet a reasonable amount for readings) and doing guest workshops at conferences, but that lifestyle tends to be short-lived and cycles around a poet’s most recent award-winning book. The rest get by with other jobs. Lots of us teach, but many more do other things, and squeeze in readings (usually unpaid) and conferences (sometimes paid, sometimes not) where they try to sell a few books when they can.

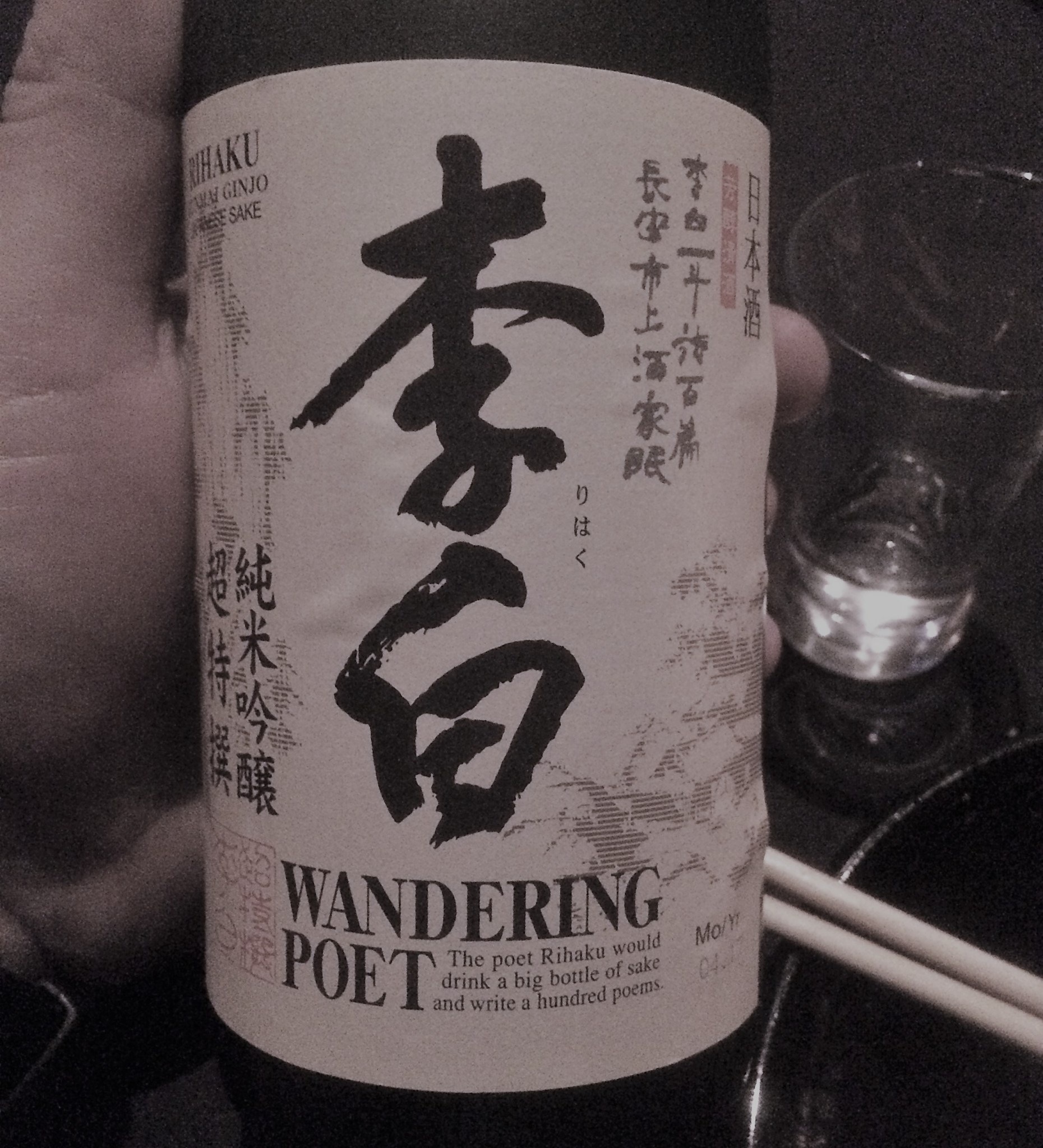

Aside from the famous few, most poets make their book money from selling them in person. Few bookstores (despite the resurgence of independent bookstores) offer little more than a couple of dozen poetry titles, and they’re mostly from large presses (large independents like Graywolf and Copper Canyon) and the year’s biggest award winners (plus some Instagram poets and Homer). Amazon of course sells everything, but that company makes it very hard for a publisher to make much of a profit, so by the time the author gets a cut, you’re looking at a year’s sales being enough to buy a case of beer, craft beer if you’re lucky.

Contests, Reading Fees and Costs

What about agents? In poetry, they’re like Bigfoot. You may believe they exist, but very few poets have ever seen one. Only a few poets in the top-tiers of the business (I hate that I wrote business, but I can’t think of another word) have agents, and those tend to only show up once the writer has already achieved success via a big award or other sort of fame. If you’re like most of us, or are just starting out trying to publish, just put the idea of agents out of your mind.

So, back to contests and reading fees, and why. Poetry’s not very profitable. Neither is fly fishing, but people do both out of a love for the thing. Since they know they’re not going to make much or anything selling a book (usually), publishers will try to bring in some of the money up front in the form contest or reading fees which then go toward paying the contest prize, and paying the editors and production costs. Without those fees, as painful as they are for both sides, many good publishers couldn’t stay in business and many books wouldn’t exist. Because poetry publishers rarely give advances anymore, the contest model can be better for poets than a straight-forward royalty arrangement, because what good are royalties if you’re mostly selling the books yourself. Of course that will vary depending on the publisher, the poet, the book and what you want or expect out of the process.

Let’s say the typical contest prize is $1,000 (some pay out more, few pay out less). I looked at my last three books and saw that I averaged 12 submissions for each one, at about $28 for each submission. That’s $336 spent getting each book published (update–I’ve way exceeded that for my 6th, still-unpublished manuscript). Some of those fees give you the winning book or a subscription to a journal, so they’re not all just lost money. But still, I figure I have to budget at least that much for my next book (see update note above). Let’s say I win one that pays me $1,000 (my last one paid more—Yay! but play along anyway) plus 20 author copies. Of course I’m going to want more than 20, so I pay the author accommodation price, which tends to be fifty or sixty percent of the cover. Let’s say the book costs $16, so my price will be $8 a copy. Pretend I buy 100 copies because I plan to do a lot of readings. That’s $800, plus the $336 I would have spent in contest fees, and I’m already $136 in the hole by the time I’ve signed the contract.

Let’s say the typical contest prize is $1,000 (some pay out more, few pay out less). I looked at my last three books and saw that I averaged 12 submissions for each one, at about $28 for each submission. That’s $336 spent getting each book published (update–I’ve way exceeded that for my 6th, still-unpublished manuscript). Some of those fees give you the winning book or a subscription to a journal, so they’re not all just lost money. But still, I figure I have to budget at least that much for my next book (see update note above). Let’s say I win one that pays me $1,000 (my last one paid more—Yay! but play along anyway) plus 20 author copies. Of course I’m going to want more than 20, so I pay the author accommodation price, which tends to be fifty or sixty percent of the cover. Let’s say the book costs $16, so my price will be $8 a copy. Pretend I buy 100 copies because I plan to do a lot of readings. That’s $800, plus the $336 I would have spent in contest fees, and I’m already $136 in the hole by the time I’ve signed the contract.

But I’ve got my book (Yay again!) and 120 copies to sell. Of course I have to give some to family and a few friends. Let’s say I give out 25. Then there are review copies. Maybe the publisher sends out some, maybe not. I’ll add another 5. Now I’ve only got 90 copies of the book left and haven’t sold a thing. How about readings—hopefully I’ve set up a lot.

Selling It

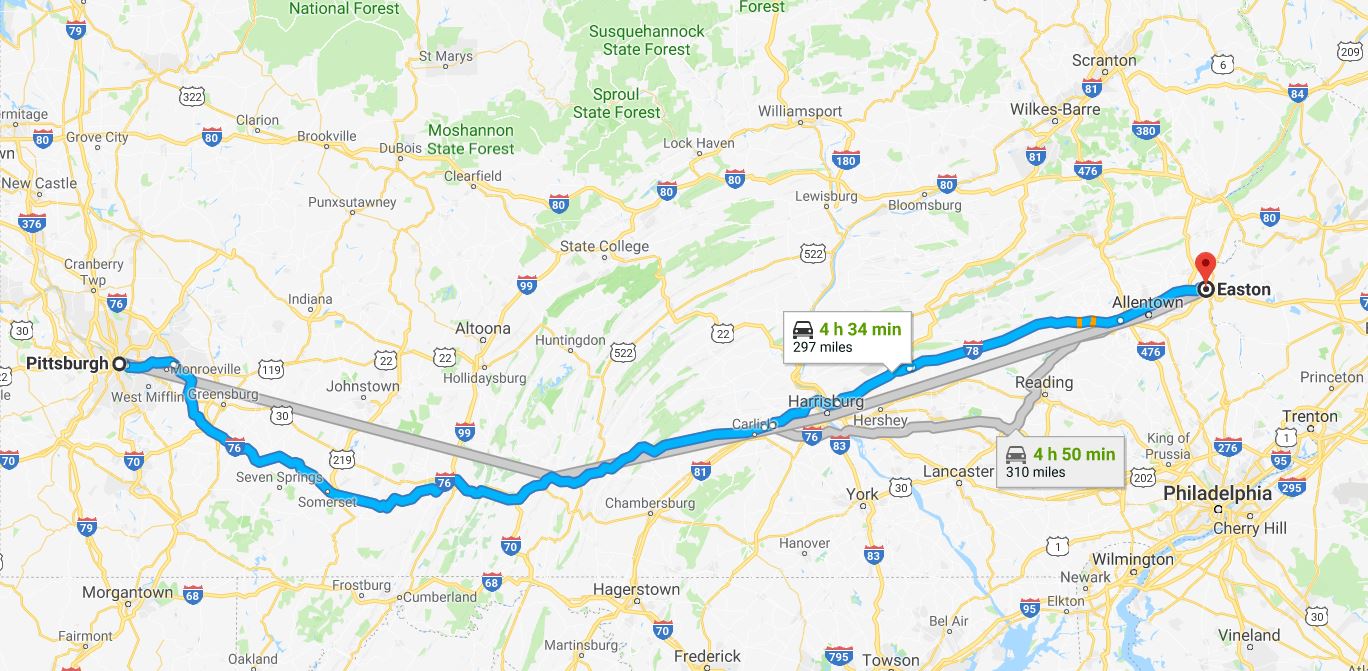

Selling books sometimes feels like selling Girl Scout Cookies door-to-door, and the only flavor you have to offer is Trios. Selling books at readings can be hard. In 2018 I did 18 readings (I had two new books to promote). On a good night I’d sell 10. At a typical reading where 12 people show up I may only sell three or four copies. And usually you feel obligated to give the host a free copy (one venue told me that was a requirement). So let’s say you drove 45 minutes to read at a coffee shop, had to buy your own coffee ($4) and pay for parking ($12), sold three copies (at $16 each minus the $8 you paid) and then gave one away ( another lost $8) and drove home to watch Game of Thrones (HBO costs $14 a month). That kind of thing tends to sour a person on readings.

What about bookstores? Bookstores are great places to read, especially if the place has a long-established reading series, but they present another financial challenge to the writer. Bookstores are in the business of selling books, and they offer you a venue and an audience, so they expect a cut. If you bring your own books, the store will usually expect about a 40% cut. So maybe you sell a few copies, and the store takes 40%, which leaves you with $9.60. But you paid $8 for those books, so now you’ve only made $1.60 per book. How many do you need to sell to make that bookstore reading worth the trip? Of course one good paying gig at a college could make up for several disappointing coffee shops. (Note: I don’t begrudge bookstores their need to make money–they have staff to pay and lights to keep on, but it’s still hard on the small press poet.)

What about bookstores? Bookstores are great places to read, especially if the place has a long-established reading series, but they present another financial challenge to the writer. Bookstores are in the business of selling books, and they offer you a venue and an audience, so they expect a cut. If you bring your own books, the store will usually expect about a 40% cut. So maybe you sell a few copies, and the store takes 40%, which leaves you with $9.60. But you paid $8 for those books, so now you’ve only made $1.60 per book. How many do you need to sell to make that bookstore reading worth the trip? Of course one good paying gig at a college could make up for several disappointing coffee shops. (Note: I don’t begrudge bookstores their need to make money–they have staff to pay and lights to keep on, but it’s still hard on the small press poet.)

So, when non-writing friend ask me how poets make money on books, I have to factor in things that aren’t directly attached to book sales. Did I get invited to teach at a conference that year? Did I teach a night class workshop? Did I serve as a judge for a poetry contest? Since none of those things would have happened without the existence of my books, I count them as book-related profit. That’s how poetry accounting works—it’s different than regular accounting.

This all sounds like a lot of grousing and complaining. Is it all worth it? That depends on how important money is to the whole scope of being a poet. To me, it’s worth it. Writing, hopefully writing well, and having a book in hand to prove it, is a poet’s marker in the ground that they did something worth saving, worth sharing and worth lasting. Every person or organization who’s helped support a poet, especially the small book publishers, the independent bookstores, the coffee shop readings and the small journals and websites are part of a network creating a legacy for something important to survive. I get value from having a book to show my family, to share with my friends, and knowing that in a few other homes, my book is also being shared—that’s an enormous reward even if it doesn’t pay for much coffee. The readings and events I do to support my work allow me to meet and talk to people I wouldn’t have encountered otherwise. It’s led to great conversations and some great friendships.