I’m happy to be conducting another online poetry workshop hosted by One Art, the web publication edited by Mark Danowski. It happens Tuesday Feb 17, from 6pm to 8pm and I’m calling it That Feeling When.

This is a generative workshop aimed at demonstrating some techniques to create poems about, for lack of better terms, vague or abstract feelings. Many poems, particularly lyric-focus poetry, function largely as vehicles to express things that can only be expressed through poetry—this is the best function of any art. In this workshop I’ll help attendees identify those abstracts and find ways to turn them into words.

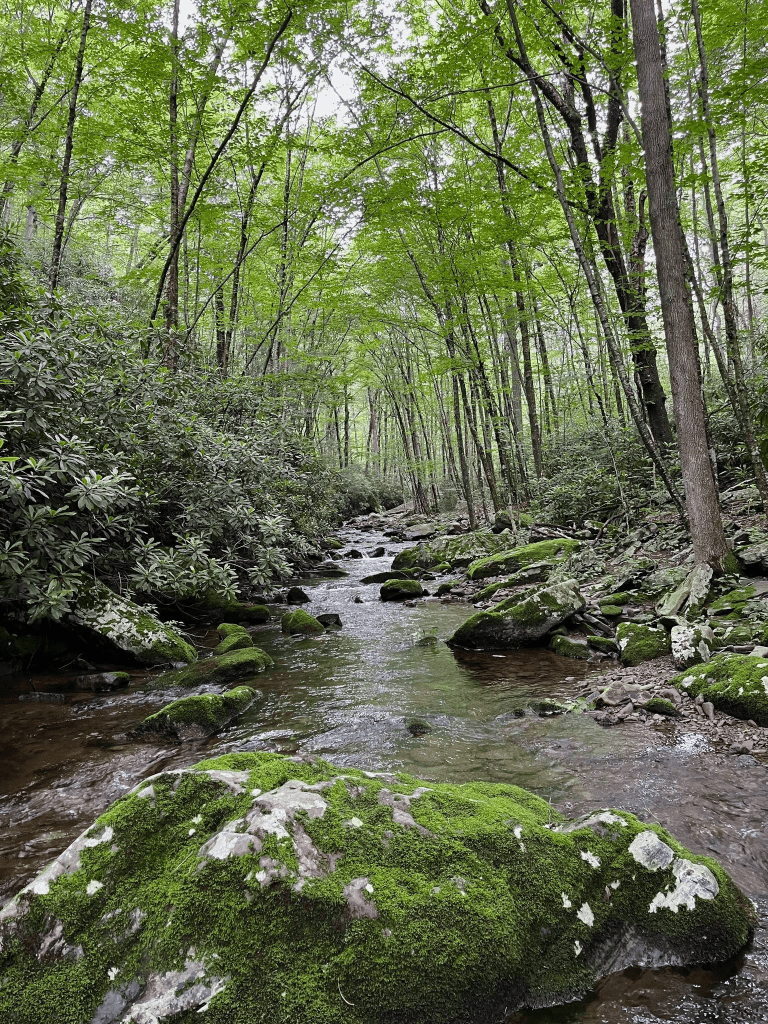

Wendell Berry’s poem The Peace of Wild Things is a good example of identifying that feeling and showing its result. In this case, the action he chooses to take. When “despair for the world” overcomes him, he turns to wild things, and the poem describes his decision and actions. This is a fairly obvious version of the approach—the feeling is directly stated, rather than left for the reader to experience–we experience the results of the feeling. For a writer, just choose anything that elicits a feeling, and write the actions you take. It could be something very situational and specific (when I watch the first snowfall of the year from my window…) or more general, like Berry’s poem.

Another approach, and one we’ll also discuss in the class, doesn’t come out and state what the feeling is. The poem may describe the circumstances of a feeling, without naming it, usually because it doesn’t have a name at all. Consider this poem by Linda Gregg. What is the feeling it conveys? I don’t know there’s a word, or just one word for it. That’s why it’s a poem. The prompt could be something like “write that feeling when you’re looking out over town and thinking of the people in the houses below, what they’ve been through and what they may want…” In this case, she describes a scene (imaginary or not? I don’t know), and a subject (is “she” Gregg or someone Gregg invents—we don’t know), but the description and setting powerfully invoke a number of feelings by their arrangement and telling.

Anyway, we’ll look at several examples, talk about how they work, and then I’ll both offer prompts and show how you can create your own prompts for future poems.

Oh, and by the way, at only $25 this is a very affordable workshop. Details on how to register here.

—

I

I